I am always writing about mulch: how wonderful it is, how good for the garden it is, and detailing some of the many reasons to apply it.

However, I didn't say anything about how to get it onto the beds: as far as actually applying mulch goes, I didn't realise that there was a technique to it, until - earlier this year - I set one of my Trainees off to do some mulching, came back ten minutes later, and was horrified by the mess they were making: they were digging out the compost with a big shovel, then heaving out great dollops of it all over the bed, apparently at random.

This left a “surface of the moon” effect, with massive craters and mounds, squashed daffodils, and smothered plants, not to mention all the sticks and rubbish sticking out of it.

Oops! I should have shown them how to do it, before leaving them to get on with it!

And as Trainees are with me in order to learn, I had to interrupt them, and explain that there was a better way to do it.

The correct technique, then, is to lift smallish shovel-fulls out from the compost heap, shaking or dropping them into the wheelbarrow.

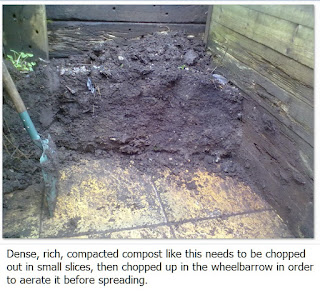

If they do not immediately crumble (and in this particular garden, our home-made compost is dense and compacted, as you can see, left!), then use the spade to chop vertically down into the material in the barrow, breaking up the clods as you fill it.

Pick out any sticks, stones, plastic labels and rubbish as you fill the barrow: sticks can be either thrown away behind the compost pens or - if they are fairly small ones - thrown into the active pen in order to go round again: but the non-organic rubbish must be put aside for disposal.

I usually arrange to leave an old bucket or a plastic plant pot by the compost pens, for this purpose.

Then, when you get to the bed or border, don't use the spade/shovel to apply the compost.

Instead, take your hand-trowel in one hand, and chop it through the top layer in order to make it light, and aerated - “friable” is the technical term. Then lift a double handful (I keep the trowel in one hand, which allows me to take a bigger scoop, and keeps it ready for use) and deal it out in an underarm bowling action. This ensures that you don't crush some tender new growth under the weight: it spreads it out, making it go further (fewer barrow-loads required, heh heh) and it give a more even spread.

It also allows you to get the compost mulch right to the back of the bed, behind the plants, without having to step all over them - you can bowl the compost towards the back of the bed, and if you have chopped it up properly before bowling, you will be surprised how it goes around the stems, rather than landing on top and squashing the plants.

"Bowling" is an especially important technique when it's recently rained: treading on wet soil will compact it, ruining the soil structure, creating a pan or crust on the top - which makes it harder for water to penetrate the soil - and ultimately making it harder for you to weed it, later in the year. But by "bowling", you don't need to step onto the bed - you can do it from the edge.

Keep chopping and bowling until you've used it all, then go back for more if necessary.

The exact same technique works when mulching with chipped bark as well: it usually arrived in large tightly-packed plastic sacks, so it's important to tip it out of the bag into a barrow, then shake or chop it until it is in separate pieces, not in thick heavy slices. Again, take a double handful and bowl it underarm onto the beds. This makes it easy to get an even covering of bark, while not suffocating any plants, and it also makes it go further.

So there you go - it's not difficult, but it makes quite a difference to the garden!

Did you enjoy this article? Did you find it useful? Would you like me to answer your own, personal, gardening question? Become a Patron - just click here - and support me! Or use the Donate button for a one-off donation. If just 10% of my visitors gave me a pound a month, I'd be able to spend a lot more time answering all the questions!!