Just the other day, I wrote about Crocosmia, which grow from what look like bulbs, but which are actually corms, and I said that I would write a quick article explaining the difference.

Does anyone care?

Apparently a few people do (*waves cheerfully*), so here we go! Brace yourselves for some botany... let's gallop quickly through bulbs, corms, tubers, and rhizomes, all of which are underground storage organs, which hold the energy which the plant needs to produce flowers.

1) bulbs

A lot of plants-which-come-from-bulbs appear very early in the year, and many of them flower before the leaves are up, or are only just up, which begs the question, where do they get the energy for all those flowers, before the leaves have barely had a chance to start photosynthesising?

The answer lies in those bulbs, those "storage organs", which put aside a whole bunch of energy (in the form of insoluble starch) (and the "insoluble" part is important, to make sure it doesn't get leached away by water in the soil, over the dormant period) at the end of the previous year, which then gets used up by the flowering stems, early in the year: then the leaves do their bit, and replace the stored energy ready for the following year.

This also describes the reason why we don't cut down the foliage of bulbs as soon as the flowers are over: I am sure you have read about the importance of leaving the foliage to die down naturally, hence the importance of planting bulbs in areas where you don't have to mow the grass until a couple of months later.. well, that's the reason why. If you cut off the leaves too soon, the bulb hasn't had time to store up enough energy to flower the next year, hence no flowers.

So, now we all know about bulbs.

Does this mean that all spring flowers grow from bulbs?

No: there are a couple of types of "underground storage organ", which all fulfil the same function, but do it in different ways.

Here's a bit of culinary botany for you, to start with: bulbs are modified leaves.

If you cut one in half, you will find that it looks very much like an onion inside - there are lots of "layers".

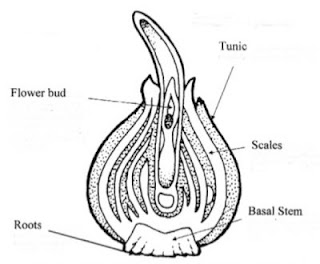

Here's a diagram - left.

It's a Daffodil, but it holds true for most bulbs.

At the bottom is what's called a Basal Plate or Stem: this is the original stem of the plant, shrunk down to a tiny short thing. Roots spring out from the underside of it, and leaves spring out from the upper side, and they have become thick and fleshy (and very short) so they form the "onion" part of the bulb. Outside all this lot, you will often (not always) find a papery brown layer, which is called the tunic, whose job is to protect the "leaves". And at the very centre, you will find the buds which will become the flowering stem, followed by the proper leaves, which will do all the hard work of photosynthesising, to replenish those fleshy leaves.

Bulbs reproduce in two ways: the flower up above can form seeds, and the basal plate, down below, can produce bulbils, which are tiny little bulbs. They can take a few years to grow large enough to flower, and they are the reason why bulbs spread in clumps: each individual bulb which you plant will, after a few years, have made a colony around itself. And that's also why bulbs sometimes need to be lifted and separated (sounds like a Playtex advert, said she, showing her age), as they can become overcrowded by their own offspring.

The analogy with an onion brings up the important point that Daffodils may look like onions, but they are not edible. They are, in fact, quite poisonous, and a few people die each year from accidentally eating them, thinking they were onions.

Now let's move on to corms, which takes us back to our Crocosmia.

Corms are modified stems, and they are undifferentiated, which means that if you cut them across, they have no layers, it's just solid.

Like bulbs, they have a basal plate - which helps you to plant them the correct way up - and they also have an outside layer called a tunic, which can be fibrous, or it can be quite smooth but with distinct rings. The technical term for these two is netted, or reticulate, for the fibrous tunics: and annulate for the sort with rings. This can be handy to know, because sometimes this is the way to tell which crocus species is which. Advanced botany! Next autumn, go and look in your local garden centre, at all the packs of bulbs hung up for sale, and look closely at the crocus section. You will be able to see the difference between reticulate crocus bulbs, and annulate ones. No-one else will care, but you will have the satisfaction of knowing more than everyone else!

Unlike bulbs, the corm is not used again the following year: instead, the plant creates a new corm on top of the old one, pushing the older ones further down into the soil.

Now we have tubers: and the easiest example is the humble potato.

You will all be familiar with the "eyes" of a spud: those are the growing points, the areas which sprout, if left in the bottom of the cupboard for too long. So you already know that tubers are a bit disorganised, compared to bulbs and corms: they don't have a basal plate, they don't have a papery tunic, and it's not at all easy to tell which way up they should be planted.

If in doubt, with tubers, just plant them any old way, and let them sort themselves out. Mind you, bulbs will likewise find a way up to the surface, if you accidentally plant them upside down, or if you just throw a handful of them into a hole in the ground, stomp the earth down, and forget all about them... yes, I did that once, and when I dug them up later in the year, they were the most wonderful tangle of shoots and roots! They still flowered. Oh, and there's this:

I wrote about this one a while back: it's a Daffodil bulb which was dug up by varmints, small rodents in the garden, and left on the surface of the pot. When it started to shoot, the shoot pushed into the soil - which is what it would expect to find, after all - but instead of growing upwards and into daylight, it grew downwards, and actually lifted its bulb off the ground!

I took pity on it, and reburied it the right way up, but it does go to show that - as was famously said in Jurassic Park, life will find a way: although that was a bit more sinister than one upside-down daffodil.

Where were we? Oh yes, tubers: no basal plate, no tunic (the thin skins of new potatoes don't count, before you ask!), no internal structure to speak of. They don't make offsets, or produce baby tubers: they either just get bigger every year - that would be things like Dahlias - or the tuber is used up to produce the new plant, which then produces a whole bunch of new tubers ready for the following year. If you've ever grown potatoes, you will have seen this in action: the original "seed" potato can often be found as a shrivelled, shrunken-head sort of thing, when you lift the plants, which has meanwhile produced a whole big cluster of beautiful firm new tubers, which we then gleefully eat.

4) and now we have Rhizomes.

These are stems which grow sideways, rather than growing upwards, so they run along under, or on, the surface of the soil. They get bigger and fatter each year, and they often branch and divide, with any one rhizome producing two new ones each year, which means they spread rapidly and exponentially.

Again, this can lead to overcrowding and reduced flowering, so every few years they can be lifted and split, as each section of rhizome will then grow into a new plant.

Here - left - are a handful of Bearded Iris rhizomes being split and re-planted, and you can see the mass of fibrous roots produced all the way along the rhizome.

You can also see how the main rhizome is producing a handful of new rhizomes at the leafy end, each of which will produce a flower the following year.

So there you have it:

Bulbs = modified leaves in layers: tunic, yes; basal plate, yes. Examples: daffodils, tulips, hyacinths, and snowdrops

Corms = swollen stem base, undifferentiated: tunic, yes; basal plate yes. Examples: crocosmia, gladiolus, freesia, and crocus

Tuber = modified stem, undifferentiated: tunic, no; basal plate, no. Examples: potato, dahlias, hemerocallis (Day Lily)

Rhizome = modified stem, undifferentiated, growing sideways: tunic, no; basal plate, no. Examples: Iris, lily-of-the-valley, canna, and ginger.

Did you enjoy this article? Did you find it useful? Would you like me to answer your own, personal, gardening question? Become a Patron - just click here - and support me! Or use the Donate button for a one-off donation. If just 10% of my visitors gave me a pound a month, I'd be able to spend a lot more time answering all the questions!!